-

Head of Research and Translation at SEDRA Foundation for Inclusion.

-

Arabic Curriculum team leader at an educational institution.

-

Worked with hundreds of Arab teachers, obtaining honourary membership in numerous committees. These specialised in developing curricula, academic accreditation and education laws for the Ministry of Education.

-

Educational consultant in many Indian and international schools.

-

The first non-Arab licensed to teach Arabic in an Arab country.

-

The author of the famous words: “Break my bones and do not break the mansoob”, “Cursing me in Fusha is more beloved to me than praising me in colloquial” and “I am jealous for Arabic more than a man is jealous for his wife.”

The Arabic Workshop Project is a pioneering and successful effort, God willing, in the field of facilitating and endearing the learning of Arabic to children and others. Its content is very interesting and exciting. Graduality and the psyche of different cultural backgrounds and ages of the contemporary generation is taken into account. In addition, it possesses a systematic design expressing full awareness and deep knowledge of the latest methods of teaching and learning languages.

I can only ask the Honourable Lord to support the leaders of this pioneering project in serving the language of His immortal Book. May He please their eyes with good success and pay them back in this world and the Hereafter.

It is a great pleasure and pride to have this conversation with you, sir. Thank you very much for kindly accepting.

You are known for your love of Arabic. What a love! You proved sincerity in your love for it and it paid you back in abundance. You became a teacher of Arabic language to the Arabs!

This love story began when you were ten years old, where you have said “your unoccupied heart met it by coincidence, and it overtook you!”. You started talking to yourself and those around you in Arabic even though they were not aware of what you were saying!

Q: How did Arabic possess your heart to this degree? Did you get tired at some point, resist it, and leave it? Or have you been as steadfast to it since its arrow hit your heart?

A: I think that I have always been sincere to Arabic. I did not betray my covenant with it since it found my unoccupied heart. It was, and still is, to me “the first sweetheart”. As the poet said:

Take your heart where you want in pursuit of love..

True love is exclusive to the first one..

No matter how many houses on earth a boy dwells into,

His longing will be greater for his first home..

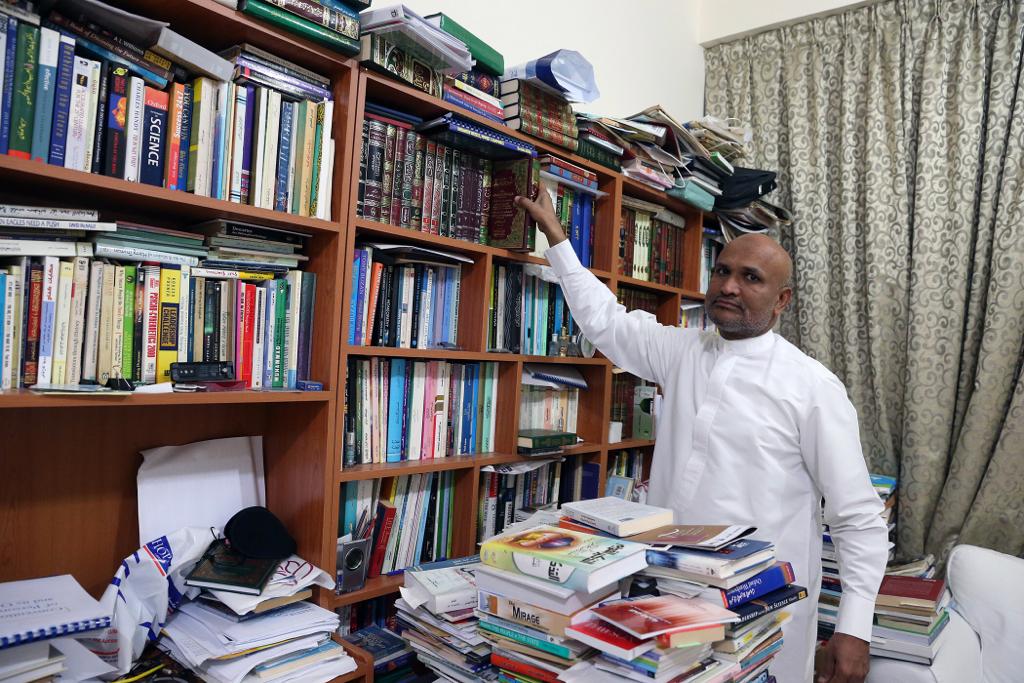

A proof of my love for Arabic is that I abandoned reading, writing and speaking in my native language Urdu between 1985-1990. Even with my family and community. During my everyday conversations, I used to interpret in my mind any words spoken to me into Arabic first. I would respond in Arabic then translate my speech into Urdu, English or Hindi! Of course, the path to connecting with my “precious beloved” or acquiring it was not easy. I suffered greatly in pursuit of my beloved, both psychologically and practically. This was partly due to my family’s poverty and also, the lack of moral support from schools and my people. Another issue was the unattractive and ineffective traditional teaching methodologies. These were prevalent at that time in state and religious schools throughout India.

Q: How did you develop your linguistic reserve in the absence of advanced curricula and the opportunity of immersion?

A: As the saying goes: “Need is the mother of invention”. As a result, I invented many practical methods to fill every defect in my path and removed every obstacle in the various stages of my journey towards enriching my reserve of Arabic. I sought to master my language skills by intensifying, multiplying and diversifying the use of available books and learning resources. The most important of these being the Holy Qur’an. It is not possible here to talk extensively about my innovative and varied experiences, whether in the field of self-learning or teaching it to others. Therefore, I will suggest one way of how to use the Holy Qur’an as an enriching source of linguistic outcome. This can be done whilst developing the skills of reading, speaking and writing in Arabic. It can be summarised as follows:

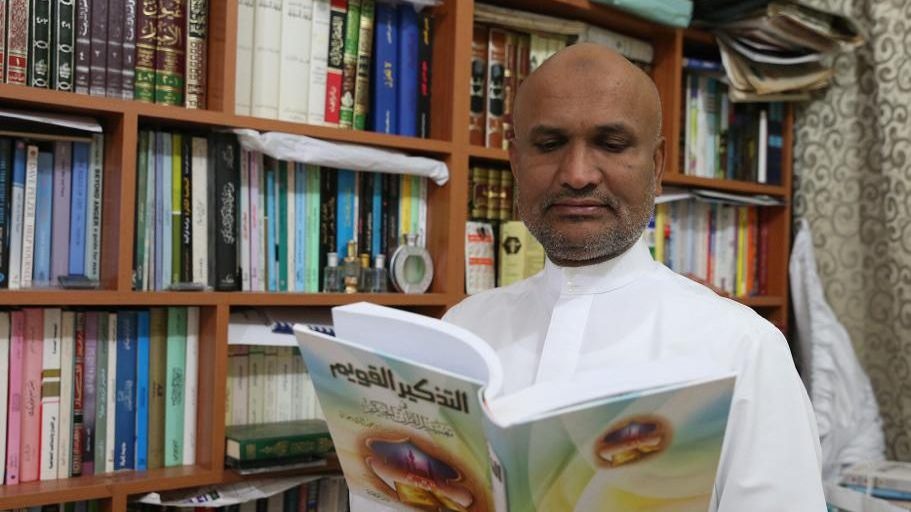

Untraditional recitation

I abandoned the familiar and traditional method of reciting the Noble Qur’an. By this, I mean where the reciter sometimes adheres to a type of recitation by observing the rules of Tajwid or by constantly moving one’s head and upper part of the body. I discovered that this habit of recitation has unintentionally become an obstacle in realising the meanings of the Noble Qur’an. Above all else, the reciter focuses more on improving his voice and melody rather than on understanding the meaning. The head and body movement accompanying recitation may only help in memorising the words. It doesn’t help in understanding and comprehending their meanings.

Tell the Story, look for dialogue

Based on the above, I decided to read the Qur’an in a high tone word by word, or sentence by sentence. As much as possible, I tried to embody the type of word or sentence used (interrogation/ wondering/ calling/ warning..etc) by focusing on rhythm bell instead of focusing on the rules of recitation such as Ghunnah (nasalisation of Mim and Nun), Madd (elongation of vowels), merging letters and so on.

For instance, there are numerous examples of dialogue in the Qur’an. There are exchanges of questions and answers between two parties. For example, between God, the Angels and Satan, between the prophets and their nations, especially Pharaoh and Moses and so on. I recited them as though I’m telling a story in front of young children. I used to embody all roles myself in the form of question and answer. Repetition didn’t bore me because I wanted to master the Arabic pronunciation and improve my fluency in reading.

Apply it

I suspect that this practice was for me a kind of linguistic immersion, on an individual level if I can say so. After a while, the result was that I started using the compositions, expressions and Qur’anic phrases spontaneously. This was according to need in the various contexts of daily life. For instance, if I saw a person carrying something in his hand, I addressed him saying, “And what is with your right or your left, O so and so?” Or if I saw lunch or dinner put on the table, I would say “Glad tidings! This is food!” And so on.

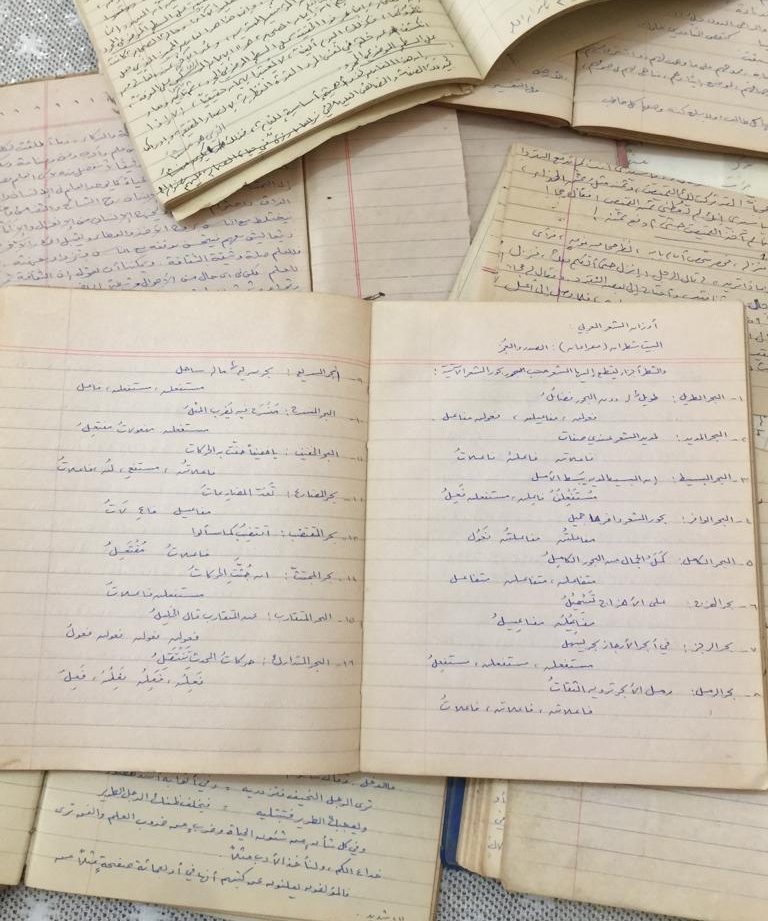

During this daily reading for an hour or more in a story or a Surah (chapter) from the Qur’an, I used to extract 10-20 words, phrases or sentences with the intention of using them in my daily conversations, both with myself and others. This was after reviewing their linguistic meanings in dictionaries or translations of the Quran. I used translations into Urdu, Farsi, English or Hindi.

Based on this experience of self-learning, I therefore developed an approach to teaching the Arabic language. Most of its vocabulary and structures are derived from the Holy Qur’an. It is primarily centered on developing the skill of conversation. In this way, Arabic becomes the tool of communication with students and teaching for all stages.

Q: What was the real starting point on your way to fluency?

A: It was the continuous vocal reading of the Noble Qur’an as described above, and for any article I could read with a focus on two things: understanding the written material and then deliberately searching for and creating situations to use the maximum amount of the new vocabulary and structures on a daily basis.

Q: Most Arabic courses and curricula are limited to books. Availability to audio materials suitable for beginners and intermediate students is also limited. How did you overcome this obstacle in India?

A: Of course, the lack of audio material appropriate to the various stages of learning delayed my language acquisition progress for more than a decade, but it did not make it impossible. If these audiovisual materials were available to me at school then I might have realised my dream of mastering Arabic much earlier. Perhaps I might have passed it on to generations of my Indian students with the same degree of fluency or even greater.

Q: Is your loved one (Arabic) as hard to reach as it seems?

A: No. The Arabic language is neither difficult nor easy. It is like learning any spoken language, or even gaining any life skill. A genuine desire to learn is sufficient in enabling you to overcome all obstacles. It’s necessary to focus your attention, commit time and effort consistently, and practise constantly. Any person can learn the Arabic language, or any other language. It is the same way you learn to walk, cycle or drive a car. Whoever thinks of something as difficult is announcing that he does not have a genuine desire for it!

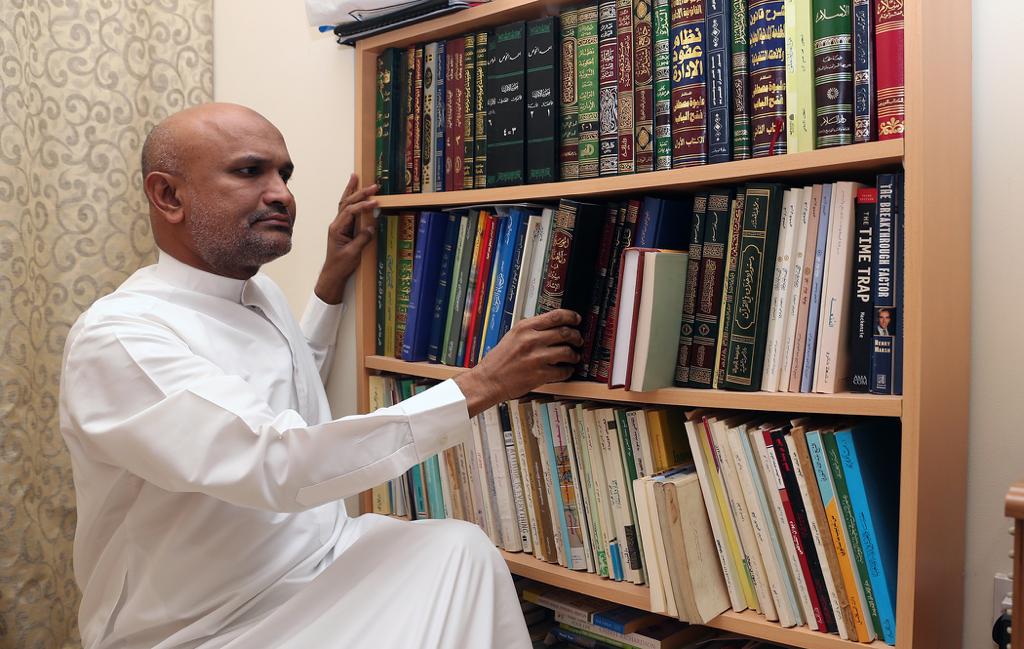

Q: You have provided living proof that attaining fluency is not impossible – what is your advice to students of Arabic?

A: Read voraciously and do not get bored with it. Be sure to understand and do not tire from it. Then apply what you read with passion. Do not care about errors that may occur or worry that others might see you as ridiculous. By application here, I mean the use of all types of sentences, phrases, structures and new expressions in the various contexts of daily life.

Q: Most Arabic courses and curricula are limited to books. Availability to audio materials suitable for beginners and intermediate students is also limited. How did you overcome this obstacle in India?

A: Of course, the lack of audio material appropriate to the various stages of learning delayed my language acquisition progress for more than a decade, but it did not make it impossible. If these audiovisual materials were available to me at school then I might have realised my dream of mastering Arabic much earlier. Perhaps I might have passed it on to generations of my Indian students with the same degree of fluency or even greater.

Q: Is your loved one (Arabic) as hard to reach as it seems?

A: No. The Arabic language is neither difficult nor easy. It is like learning any spoken language, or even gaining any life skill. A genuine desire to learn is sufficient in enabling you to overcome all obstacles. It’s necessary to focus your attention, commit time and effort consistently, and practise constantly. Any person can learn the Arabic language, or any other language. It is the same way you learn to walk, cycle or drive a car. Whoever thinks of something as difficult is announcing that he does not have a genuine desire for it!

Q: You have provided living proof that attaining fluency is not impossible – what is your advice to students of Arabic?

A: Read voraciously and do not get bored with it. Be sure to understand and do not tire from it. Then apply what you read with passion. Do not care about errors that may occur or worry that others might see you as ridiculous. By application here, I mean the use of all types of sentences, phrases, structures and new expressions in the various contexts of daily life.